a story of ledbury

what led us to now. and how …

It’s been 43 days and 11 hours since I last set foot in Ledbury (Herefordshire, England). It’s what “days.to” says, at least. I googled it, just to make sure I got it right. I have been meaning to write this since the beginning of July 2024, but life happens and we get carried away by whatever comes our way. And yet now, here I am, 2,728 km away from Ledbury. This time around, Google Maps says so. It also states that it takes 477 hours to walk the distance. I’ve walked my fair share of kilometers, but I won’t take it that far.

There’s this dependency on electronics these days that I fight my own battles with. Be it taking photos of every single thing or looking up directions without making a single effort to use one’s bearings; I try not to use my smartphone too much, whatever “much” means in this context. I like to remember things as they were, even if memory tends to obscure facts, even if time washes away their vivid clarity. In Ledbury, I kept snapping to a minimum. I took photos that would act as a springboard to remember significant moments (while using my phone to navigate my way around). And so, 43 days later, I am writing this through my memories of a lovely stay in Ledbury one photo at a time. As for the rest, the gaps are filled with impressions of a mood I long to carry with me and linger on after the cooler weather has worn away. Much like reading a book and not remembering every single detail, but knowing the story left a lasting mark and a pleasant aftertaste.

Living for three days in such a city of books was a pleasure, and an honour. When setting foot there, I could already feel an air of festivity taking over. As I always do, I went for a stroll to get accustomed to my surroundings. Mistaking the town for a village or even a city, I was reminded by locals of the smallness of it. I was in awe of the beautiful buildings. Who would’ve said that buildings would leave such a positive impact on me? Shops of every kind lined the main street: an ironmonger, an eye centre, a boutique, a supermarket, a ceramics shop, a vegetable monger, a pharmacy, a charity shop. All businesses operate from tiny and humble spots that boast their style while preserving a building that withstood time.

The people of Ledbury are a pleasure to be with and talk to. They know books, stories, legends, history, and music. Time seems to not have shaken them except for imbuing their person with knowledge and a sense of awe and wonder. Locals still send emails whenever they remember an anecdote or relic related to Malta. Audiences were indeed much intrigued by the Maltese language. What a strange feeling — to talk in your native tongue to an audience who does not understand a single word. It feels like you are talking to yourself, and somehow, you still feel as if you are creating connections. Because words are more than mere sounds and meanings. They are uttered with intention. They carry emotion, and that emotion resonates every single time, in different manners, in settings unlike the ones before. From halls to churches, poetry flooded this town that comes alive (more than usual) each year during these poetry days.

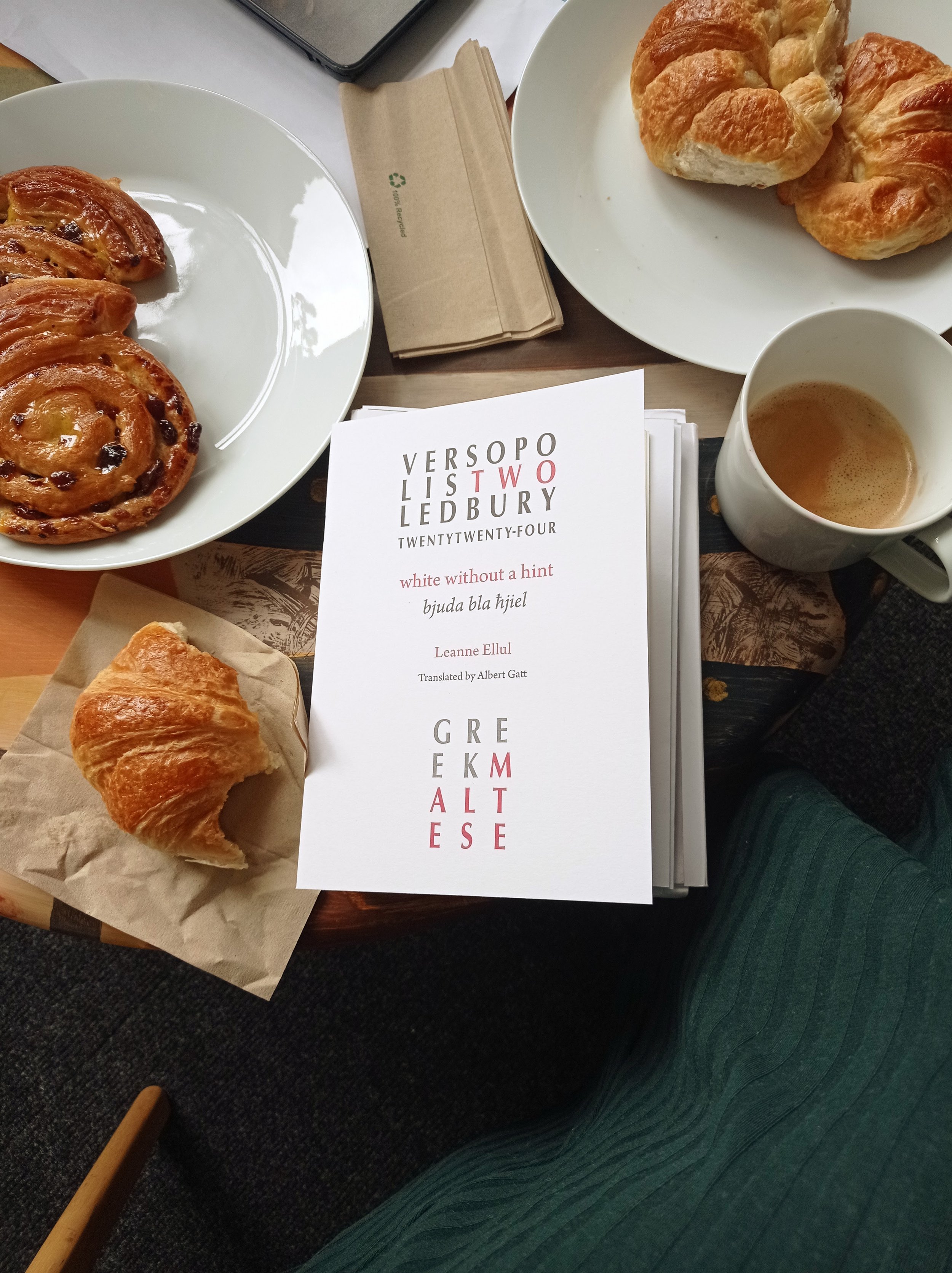

I visited Ledbury for the Ledbury Poetry Festival on behalf of Versopolis. This year, the Festival took place between the 28th of June and the 7th of July. I was invited to be part of two events. The first event was a conversation with Alexandros Chronides from Cyprus led by Kimberly Campanello, a Ledbury Poetry Trustee, poet, and Professor of Poetry. During our conversation we touched upon the musicality of language and the politics of translation, the history of Maltese poetry, and women, amongst other topics. I also had the privilege to read some of my poems. This event also served as a chapbook launch, a lovely initiative by Versopolis whereby each author invited to a Festival is translated into that country’s language and published in a little book. I had the privilege of working with Glenn Storhaug from Five Seasons Press who did a lovely job in producing this little book.

The second event was a twenty-minute talk. I was given free rein, and so I chose to tread the realm of trees. Here is what I had to say on the day.

-

1. Introduction

There was a time when the tiny island of Malta in the middle of the Mediterranean was much greener. Years and years ago, indigenous forests covered the island. At a time when galleons flooded the Mediterranean, trees got chopped to build ships, but also for agricultural purposes. So as far as I remember, Malta was never an Italy or France, say Umbria or Hautvillers, to begin with. In my memory, it never boasted vast expanses of land like those of other much bigger countries.

Malta is a tiny island in the Mediterranean Sea, spanning 316 square kilometers, between Italy and Libya. It boasts of the sea surrounding its shores but lacks as many green territories. It compensates for such a lack of verdant landscapes with manmade green areas, such as Buskett (from the Italian "boschetto"), one of the few woodland areas we have on the island. It was planted by the Knights of Malta to serve hunting purposes.

One would think that having so many few trees, we would take care of them. Yet, somehow, we give our backs to these oxygen-bearing pillars. As I wrote in my 2021 essay entitled “Lack of” and published in Are We Europe: “Then, as I curiously look through the louvers, the last tree standing on the opposite side of the road seems dissected. I cannot help but think it is a synecdoche for the rest of Malta: 2,418 protected trees have been uprooted since 2018. It is not a sight to be jealous of.

Greenwashing has become the order of the day, and above all, the poeticized prophecies of our Romantic poets came to be truer than true. I don’t believe that poetry can change the world, but when poetry rings so true to its time, it becomes like a soundtrack on repeat, echoing realities that demand to be heard. Poetry might not bring about drastic changes but it can ponder crude realities and in turn move us. It can be a catalyst, an enabler, a starting point.

I will now transport you through three main periods of our literary heritage, hence the title inspired by the phrase “on the count of three”: the Romantic period, the Modernist period, and the Post-90s era.

2. The Romantic period

The Romantic period in Malta spanned from the early 1900s to the mid-1960s. This period was dominated by white male writers with a religious proclivity, both as clergymen (like our national poet himself, Dun Karm Psaila, and others like Dun Frans Camilleri) and merely as believers. Anton Buttigieg was at the forefront of eco-poetry. As he claimed: “I am known as the Poet of Nature since nature is a recurrent theme in my poems.” His nature-concerned poetry, like that of fellow poets of the time, celebrated landscapes and animals, from the micro to the macro. There was a strong emphasis on looking after what we have because what we have is a gift from God. Despite the religious message, the strong prominence on protecting our natural landscape read as a strong message, as a warning for what was to come. At the time, poets also borrowed elements from the natural world to give voice to their inner feelings or to describe a scene — its beauty in all of its simplicity. One of whom is Mary Meilak, another Gozitan poet, who sang of sunrise and sunset, small creatures, and the pitter-patter of the rain. Through her poetry, Meilak shows how attuned she was to nature around her through all of her senses.

3. The Modernist period

The Modernist period, which came about around the National Independence in 1964, lingered till the 90s or so. The warning of our forefathers was being seen as a prophecy becoming reality. Modern poets, with their fierce nature of going against the grain of content and form, still elevated nature. They emphasized the beauty of it and lamented what was being lost and what was already lost to that point. A notorious prose poem of the time is by Victor Fenech, entitled “Iż-Żabra”, which translates to “The pruning”. The poem recounts the event of tree cutters (represented by pirates) assailing the tree and raping her (personified as a woman) of her dignity. Other poets (once again, male, poets like Marjanu Vella and Oliver Friggieri) lamented the loss of nature and protested against the buildings that were mushrooming on the island, especially in the late eighties, a trend that never slowed down. As quoted in an article in the Times of Malta by Neville Borg (October 2023): “ ... a staggering 26% of all occupied homes in Malta, some 55,500 homes, were built between 2016 and 2021.”

4. The post-90s era

On the count of three? Having accounted for the small amount of trees we have got through these poetical testaments, we might want to count what is left of the little amount of trees we had to begin with. We can start by counting ourselves unlucky. We can start by blaming our greed, not for trees, but for more and more buildings because, as things stand, property is the way forward to making money.

Poets in the post-90s era till today feel disillusioned. Their poetry speaks of the beauty of nature against a background of what is lost. Poets like Marlene Saliba poeticise the trees in the grander scheme of things. Her poetry is entrenched within the bigger universe and her understanding of nature goes beyond our tiny island, as can be read in part of the poem “Trees”.

Marlene Saliba - “Trees”

Hand in hand in the thick, thick wood,

conversing with the nighy

we enter dreamtime ...

Our feet, our roots well grounded

within the soil of mother earth,

gratefully and joyously

we receive the rays of the stars.

We hold an understanding

in our existence, our trunks, branches;

these branches that want to heal

the wounds and pains of all mankind …

Malta is now seen not only as part of the Mediterranean or Europe but also as part of the world and the cosmos. Hence, what we lost, leaves a deeper wound, a deeper gap that time cannot heal. Other poets like Maria Grech Ganado turned towards our myths, for instance in "Gaea", personifying the Greek goddess of the Earth, and incisively asking: “What legacy will you leave to your people?”

Contemporary poets, younger poets that are mostly female poets, still lament this loss. Their poetry is also imbued with personal memories and retellings of the natural elements intertwined within their stories. Claudia Gauci, in a poem translated by Albert Gatt, muses on “a soft orange falling from the tree,” which echoes other personal feelings, making her poetry lyrical at its best.

Claudia Gauci - "Why don’t you take some paracetamol?"

‘Cause you’re the only thing that cures me. And yet

I lose you every time I try to hunt you down

so many times you’re in my head, soundlessly stirring like a lizard,

slipping away as soon as I raise a hand to my temple tunnelling

deep where I can’t see or feel you anymore.

I stand still in the garden, listen out for you -

a soft orange falling from the tree,

a ripe plunge roused by rain on travertine.

I hear you now.

Havoc of a lizard under siege from ants in silent hoards.

Simone Inguanez’s poems take on a similar stance as those of Claudia Gauci. In "the falling trees are falling trees" translated by the poet herself and Maria Grech Ganado, trees are present in the form of a metaphor, but also a presence strongly longed to be felt, desired, and longed for.

Simone Inguanez - "the falling trees are falling trees"

the falling trees are falling trees

in the long run – the first white hair

and my tummy rolls to peep

over my Levi’s – today my legs

tire of carrying me, why should it matter?

while you rubbed my back – hands pressing down,

leaving red burning trails, you ran out of breath –

now you pass your fingers through my hair

you rest your head on my naked breasts

and let your eyes close – sleep –

when you wake, take me to grow old with you

man, i won’t forget – the taste of apples

in your kisses, and the dew in your sleepy eyes.

the four seasons are ours: we start with spring;

spring opens up; grows even lovelier

and at its ripest–

Albeit that all poetry can be political, some poetry is more political than others, thought this might be a topic for another time. Clare Azzopardi’s poetry rings true on so many levels. It is romantically personal with tinges of the political. Her body of poetic work speaks of the political in terms of narrating the women’s body, and the political in terms of lamenting nature’s loss. Let us take as an example the first part of the poem "Autumn”, translated by Albert Gatt.

Clare Azzopardi - “Autumn”

1

what are you like?

you bring me to this place, introduce me

to her woman behold the tree

tree behold the woman

and then you leave me

rummaging through words that came before

valedictions culled on purpose

from the land I left behind

by her shapely form I am misshapen

my fragile hips my trembling limbs reaching for her stately boughs

that sprout

new blossoms on my lips

I sit for days and days and days beside her

this guardian of the waterway

falling

I fall for into you

would you bear me, borne in your form?

and once again I let me

try to speak to you

the words of where I’m from

the land of once-upon-a-time the story of how there came to pass

a thousand and one builders

upon an ancient land

and headstones bearing pictures of trees felled or dead

the sun’s glare in my eyes

I’d nearly forgotten

how hot how merciless it’s become

how like you there are none

I’ve given up chasing after shades

and again again

I try

I swear I’m dying to tell you the story

starting with that once-upon-a-time that single time just once

there was one womb and a womb there were two

one barren the other bearing an unseemly weight

and once-upon-a-times ensnared in the roots’ tangle

I try to tell my self

can you hear the once-upon-a-time there was no once not one

and

I’d have gone on if only if only

I hadn’t felt you shifting

I’d have gone on to tell you

of the womb hang on, which one do you want to hear about?

you brought me here

in this other expanse of summer

brought me by her side held out my hands which it adorned with boughs

in pigments that have seeped into my veins like love like yours

no need for you to say how much

This poem opens up to the outdoor space as much as it focuses on the personal space; to me, it became personal to the point that I tattooed a verse on my arm. Clare Azzopardi, like other poets of her time — our time — scoured the world, and so she writes from a point that isn’t just gazing at some navel, but also outwardly toward the rest. Similarly, because she now spends most of her time in another country that is not Malta, her look upon Malta comes also from a distance, hence, her strong tone of criticism coupled with that of longing. Other poets who like Clare Azzopardi are Maltese and live abroad, namely in France – Elizabeth Grech and Nadia Mifsud – also have poems dedicated to trees entitled “autumn”. It must be a special season for our contemporary Maltese female poets.

Here, I must make a parenthesis to refer to male poets of our time who strongly protest nature’s demise, namely Adrian Grima and Immanuel Mifsud. Their poetry is widely read and even quoted on placards during environmental protests. Allow me to quote Albert Gatt, a friend and translator to the major poets of our time, from an interview for Modern Poetry in Translation about a special issue that was published last year: “But, you know, there are concerns which, which I feel are coming out in contemporary Maltese poetry, which are shared by, by a large number of people, including some of the people that I’ve translated for this issue. So Clare (Azzopardi), for example, was writing about trees. And trees are one of the things, which are, hotly contested in this country because they tend to disappear and make way for, you know, other kinds of development. Construction and so on … Clare has a, has this romantic streak underlying the work, I feel, where, trees take on a certain significance of permanence. But they’re also sort of these ancient and storied creatures with all kinds of narratives that get intertwined with those of human beings. Adrian (Grima) is far more overtly political …”

I would like to end this poetry-essay-crit montage with three tree poems of mine translated by Helena Camilleri; one of them is published in Modern Poetry in Translation — Call the Sea a Poet: Focus on Malta. These poems are part of a series of poems celebrating and/or lamenting trees in Malta, Gozo, and abroad, entitled Il-Manifest tas-Siġar (The Trees’ Manifest, in English). Some of these poems were published in a Maltese language chapbook and continue to be published in several journals in English. In the meantime, I am still writing more of these tree poems … which means, that Ledbury might serve me as a starting point for one such poem as well.

As for the rest of my time, I spent it at the Ledbury Poetry House flipping through books, eating cake, and chatting with lovely poets whom I admire and have had the honour to meet there. It was lovely to meet so many students who took the time to volunteer during the Festival. Students are encouraged year in,year out to volunteer at this festival whereby fresh blood is ensured for years to come. Afternoons were spent chatting with Alexandros who insisted on being called Alex, exchanging stories and finding so many similarities in personal stories but also national histories. One of the evenings took the form of a cider supper: “Every year, Ledbury Poetry Festival hosts a cider supper for its visiting poets, in honour of another cider supper that happened five miles away and a hundred years ago.” During the cider supper, I had the honour to meet Amy Howard, the newly appointed director of the festival who welcomed us with such warmth. The same can be said for the lovely Sabeen Chaudhry whom I had been exchanging emails with for months before and was overjoyed to meet in person then.

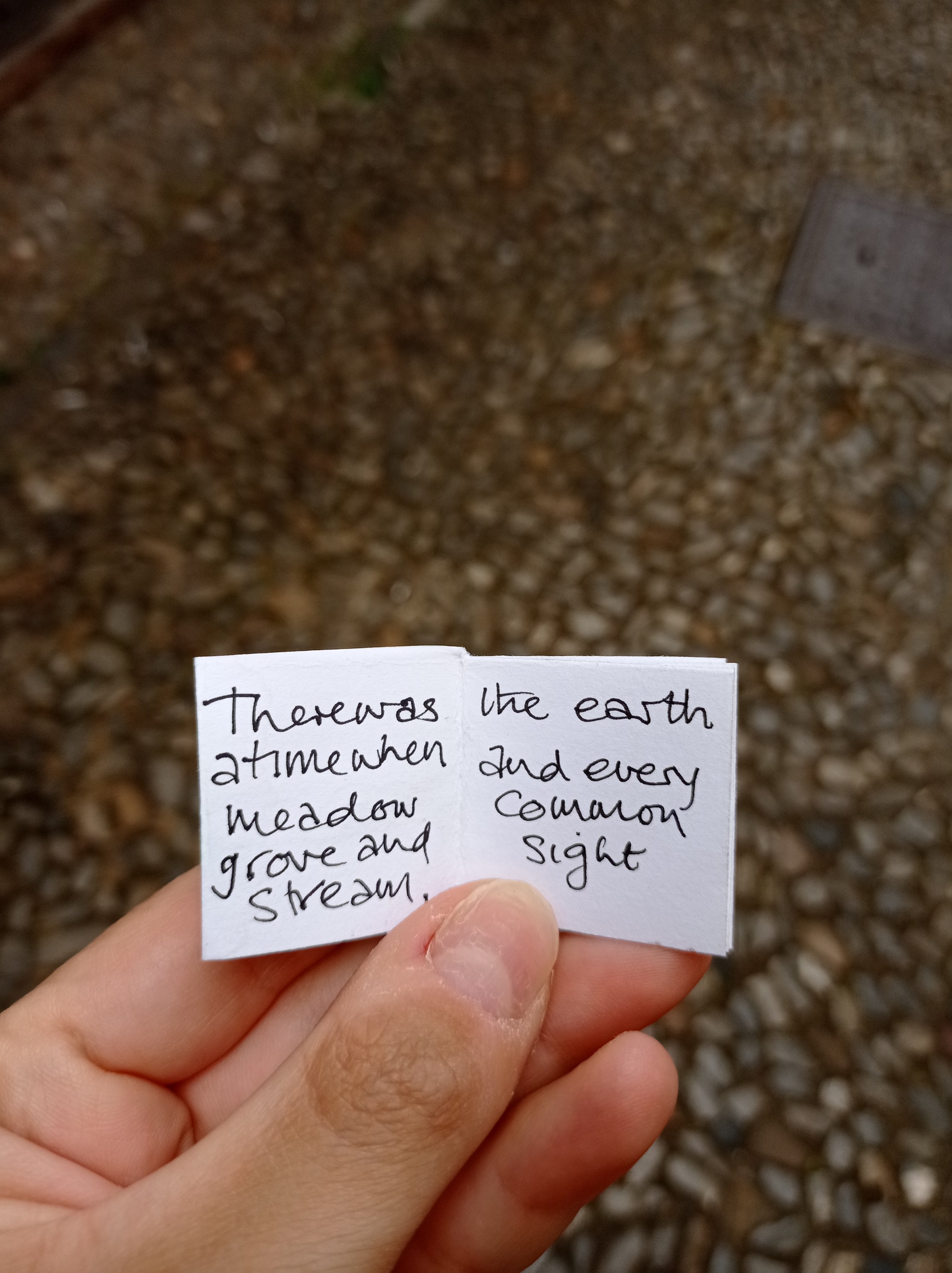

My much-beloved host, Caroline, gave me a lovely room, and I was overjoyed that the household, besides residents of the human kind, had a resident of the canine type. After one of my morning walks, Caroline advised me of the Ledbury walking trail, and for the two consecutive mornings that followed I took that circular path. Wandering the streets of Ledbury led me to see loads of placards saying ‘Ellie Chowns’ whom I later learned is a British Green Party politician, serving as Member of Parliament for North Herefordshire. A lot of Ledbury residents were in fact campaigning for her to get elected in the UK. Walking across the cemetery, I was surprised to see an over-the-top monument for what I assumed was a recently deceased grandma. Never in my life have I encountered such theatricality in the context of a cemetery. It was a joy to meet Philip Weaver, the one with the little books, as he calls himself, at one of the museums who kindly donated one of his small books to me. It is one of eight hand-made, small books he made on his eightieth birthday. Although I did not get the opportunity to visit the Butcher Row House, one of its members kept in touch and they did send me information about the HMS Ledbury that “was involved in bringing the damaged oil tanker Ohio into Valletta harbour”, as Barry Sharples claims. I also got to visit the homely Ledbury Library at The Master's House, which started its life as a home for the Master of St Katherine's Hospital.

The way back to Malta was not without its bumps and humps. There were train delays, understaffed journeys, and overcrowded spaces. My way back reminded me of Robert Frost’s verses:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Having been in Ledbury could be seen as a coincidence or a result. A gift. I still don’t know what led us to now and how, but I am ever so grateful to have had the opportunity to live three days overflowing with poetry. I long to visit Ledbury again someday.

Heartfelt thanks to Versopolis and Inizjamed, and, of course, Ledbury, for making this happen.